INTRODUCTION

by Miriam Isaacs, Ph.D.

This website, in its initial release, contains over sixty songs drawn from the Ben Stonehill Archive. The Stonehill Archive totals over one thousand songs, and over time we will be working to put all of them up on this site. This project was undertaken during a fellowship I held at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, where I worked closely with the museum’s musicologist, Bret Werb.

What Ben Stonehill Did and Why

In 1948, Ben Stonehill, a lover of Yiddish, was aware of how much had been lost to surviving Jews in terms of cultural heritage. He took on a project on his own, to obtain and lug heavy recording equipment from Queens to Manhattan. In the lobby of the Hotel Marseilles (West 103rd Street and Broadway on Manhattan’s Upper West Side), Stonehill recorded over a thousand songs from Holocaust survivors, who were being temporarily housed. This website is a tribute to him and to his performers.

Ben Stonehill and His Sons, 1948

Courtesy of Lenox Stonehill and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

As a working man, Stonehill did not have the time to transcribe and translate the songs he had collected. He had it in mind to write his own book, which was to be titled, “Legend of a Yiddish Song Collector.” His act of dedication and personal involvement with refugees is important, not only because of the many treasures he gathered, but because, by taking the time and trouble to record the voices of survivors and speaking to them in their own language, he was affirming their own identities. He and others let them know that some in America knew their language and that some cared about the world they had left behind.

Stonehill’s early death from cancer in 1964 made that project impossible for him to complete his project, but he managed to leave his legacy by donating the collection to the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center, personally supervising the transfer to tape. The collection has been digitized by the Library and is now housed in the American Folklife Center, at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the YIVO Institute and Yad Vashem. The New York City-based Center for Traditional Music and Dance has graciously offered space for this collection on its website, through the Center’s An-sky Institute for Jewish Culture.

Why These Songs Matter

I have taken on this project because I believe that these songs offer window into the world of refugees. What was their repertoire, what did they choose to present and how did they frame it? We hear, in these hours of recording, a bygone world of the survivor subculture.

The process of singing in community, even though temporary community, has healing powers and this group did not have the luxury of therapy. Many of the songs sung by DPs (displaced persons) in the immediate postwar period address the emotional difficulties of coming to terms with the war’s effects, with the survivors’ questions of how to move forward. The songs were recorded in a semi-public place, a hotel lobby. By three years after war’s end, survivors were still looking for old friends and family but making new ties, looking for mates, and marrying. They formed their own inner communities, a process that had begun in the DP camps.

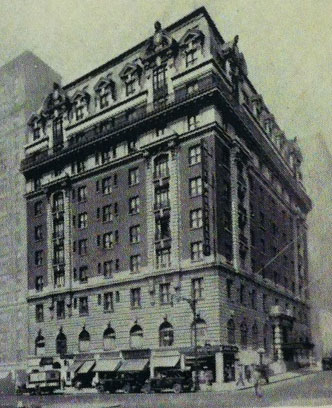

The Hotel Marseilles, New York City

Stonehill’s record of sound brings to us a kind of time capsule and being able to listen in gives one an understanding of the inner world of the survivors, their diversity, their moods and memories. It is a snapshot taken only a short time after liberation, before pressures to Americanize and forget what had happened took away some of the inclination to express what had happened to them. Songs were the vehicles, often, of conveying their stories.

Literature on the importance of songs makes it clear that music was a form of spiritual resistance. Survivors busied themselves, during and after the war, in composing songs and later collecting and compiling them. The individuals engaged in this activity performed an important social function. The composers, singers and collectors were lauded and valued by their fellow sufferers and have since become icons in the ever-shrinking world of Yiddish lovers.

The Importance of the Year 1948 – Understanding the Context

While the war officially ended in 1945, in fact, for most of the Jewish survivors, the aftershocks were still felt. Many were homeless, bereft. Meanwhile, the global dynamic shifted and they were caught up in that shift. Yiddishists formed a significant conference in New York City in that year, to assess what was left of the Yiddish world and try to rescue what they could. Shmerke Kacherginsky, one of the important voices in this archive, came to New York for this event and recorded songs for Stonehill. Meanwhile, the state of Israel was formed– many of the songs have Zionist themes, though they were performed in America. The Soviet Union was persecuting, killing, Yiddish writers, and the Red Menace was a force to be contended with in Europe. Many Jews who had formerly been communist or socialist were reevaluating their political loyalties. In that same year, Yiddish writers in the Soviet Union were being persecuted. Those who once had communist loyalties were often disillusioned. Others had Zionist ideals and now there was a new country. Other singers were from out of the yeshiva world and new communities of orthodox Jews were forming in the New World. Still, many DPs were still sitting in refugee camps in Germany and elsewhere. Such was the climate in which these singers were living, with one foot in America and many longings still for what they had lost in the old world.

About the Songs

After working on the songs of the Stonehill collection for three years now, I have excavated only a fraction, a third at most. My reactions to the materials have shifted over time. My initial reaction, upon reading the list of the songs’ first lines, a list that Stonehill himself had made, was of a longing for home. That meant both the lost homes from before the war and a longing for new homes. I think of these songs as voices from a lost world, like Atlantis. The tracks, as mp3s, are many many more that the transcribed songs. I have spent many months listening in, and have segmented many tracks from the continuous stream of sound to organize them thematically.

Below is a categorization of the songs that are transcribed. Of the over a thousand songs Stonehill collected, I have only tracked a goodly portion so more remains to be done from the nine reels and 39 hours he collected. I hope I have made a good dent.

Video of Miriam Isaacs’s Lecture at the Library of Congress

About the Stonehill Collection, November 13, 2013

Categorization proved tricky. Some are clearly love songs, some fall neatly into religious traditions. But the bulk of the songs are clearly responses to what had just happened to them and to their whole destroyed world. I have grouped songs roughly by theme, sometimes cross-listing them. Stonehill created a handwritten list of the first lines of the 1052 in the order in which they were gathered. Some songs are sung more than once by different singers, with some variation, reflecting a folk process.

The titles of the tracks mp3s, list the songs by a shortened version of these first lines most of the time, and changed to standard orthography, that is, unless the song is well-known by title. Stonehill asked the singers to write the first lines of the songs on little slips of paper, which they brought in and from which is list derives.

I here list songs roughly by theme, identifying only the ones transcribed and translated. Some songs lend themselves to more than one category. While many of the songs deal directly with the experiences of the camps, ghettos or partisan life many more reflect the singers responses to the war in indirect ways. Thus, songs from before the war that philosophize about old age, or deal with loss of loved ones or home provide an emotional release for the great loss almost all the survivors felt.

If you have comments or questions about the website please contact prushefsky@ctmd.org